It was time to take another trip. We had planned to go to Germany, Switzerland, and Spain, but we had to limit the trip to Germany and Switzerland. Here’s why: We had to wait until we had been out of Schengen for 90 days, so the earliest we could go to a Schengen country was January 13. Plus, Michael wanted us to return to Tunisia no later than January 26 because they were going to work on Seahike (sand her bottom and apply new antifoul paint) “sometime in late January.”

In the end, we had a total of 10 days for our vacation. Due to available flights and weird extremes of costs, we started in Munich, then went to Switzerland, then went back to Germany to Berlin, then to Monastir. Today’s blog is about our first few days of the trip, in Munich and Ulm.

We first want to give a shoutout to Hotel City Demas in Munich. It is a lovely hotel, with friendly staff, and is within walking distance of lots of stuff. We arrived later in the day so our main goal the first night was to go to a beer hall. We got a nice night-time view of the Neues Rathaus along the way. Here is our hotel and Neues Rathaus (which we visited again in the daytime):

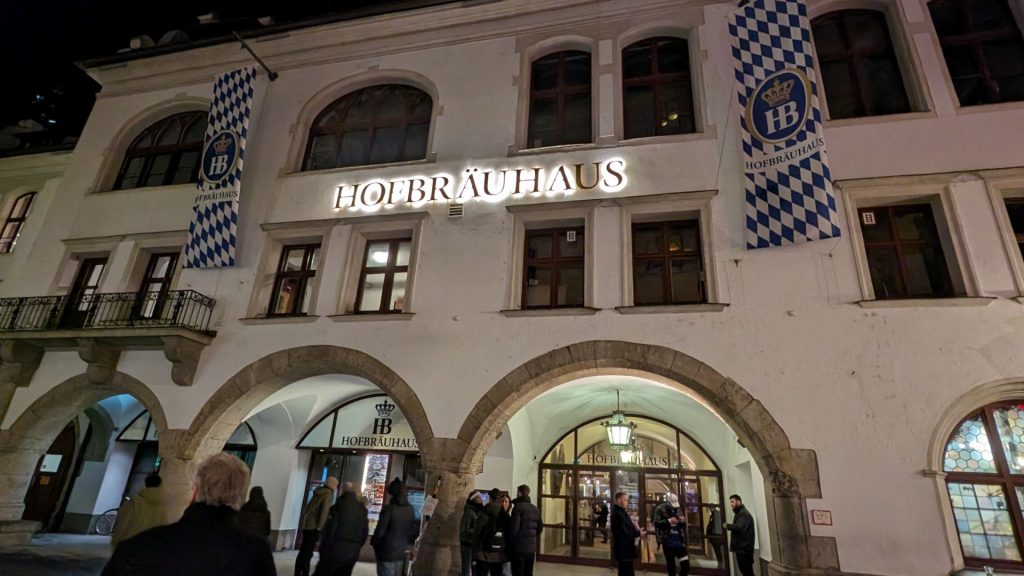

The beer hall was fun. You just grab any old table and plop down. We were fortunate to plop down next to two friendly gentlemen, and not far from the little band. The beer, music and company were all excellent. We ate something, but I don’t remember what it was.

This is where we went: Hofbräuhaus München. A legendary history. After centuries of producing beer for the royals, in 1828 the Hofbräuhaus was opened to the public by King Ludwig I of Bavaria. The beer hall quickly became the center of public and political life in Munich, counting famous names such as Mozart and Lenin amongst its regular customers.

The next day was “castle day.” We took the Flixbus to the most photographed castle in Germany: Neuschwanstein Castle, and its neighbor, Schloss Hohenschwangau. I learned that the only really good pictures of the castles are taken from above. That said, we captured a couple of nice shots and enjoyed the tours. We couldn’t take any interior pictures of either castle, which is a shame, because the interior (especially of the latter) is stunning! But no pictures would do them justice anyway.

Neuschwanstein Castle is a 19th-century historicist palace on a rugged hill of the foothills of the Alps in the very south of Germany, close to the border with Austria. The main residence of the Bavarian monarchs at the time was in Munich. King Ludwig II of Bavaria felt the need to escape from the constraints he saw himself exposed to in Munich, and commissioned Neuschwanstein Palace as a retreat but also in honor of composer Richard Wagner, whom he greatly admired.

Ludwig chose to pay for the palace out of his personal fortune and by means of extensive borrowing rather than Bavarian public funds. Construction began in 1869 but was never completed. The castle was intended to serve as a private residence for the king but he died in 1886, and it was opened to the public shortly after his death.

But the most important thing about it (is it?) is that Disney’s Sleeping Beauty’s Castle was inspired by it, as was Cinderella’s Castle. The castle’s dainty turrets and romantic views, as well as its cylindrical towers and Romanesque style made it the perfect architectural model for both Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty. Now you know!

Here is some more info about Ludwig (interesting character!) from discovery.com:

Ludwig grew up down the street from his future fairytale abode in Schloss Hohenschwangau. He became king of Bavaria at just 19 years old. The young king spent the majority of his time wrapped up in Romantic literature and operas, especially the works of composer and fellow German Richard Wagner. Ludwig began building Neuschwanstein Castle in honor of Wagner in 1869. Its third and fourth floors reflect Ludwig’s love of Wagnerian operas and feature decor inspired by many of the composer’s characters. The castle’s name itself directly translates to “New Swan Castle,” in honor of one of Wagner’s characters, “the Swan Knight.”

Yes, the castle is whimsical and grandiose, but it was certainly an anachronism for the relatively modern style of the 19th century. For a frame of reference, the Neuschwanstein has automatic flushing toilets and a central heating system. It’s only about as old as the Eiffel Tower. Ludwig commissioned the strange castle simply because he admired Romanticism and the Byzantine style. As for the castle’s placement at the top of a hill? Completely unnecessary. He didn’t need to see approaching armies; he simply enjoyed the view. The king also built himself a grotto, which was made into a private theater where he could watch Wagnerian operas. The grotto includes a fake waterfall, stage lights that change colors, and a wave machine. He often had someone row him around in a gondola during performances. Needless to say, Ludwig’s eccentric interests and expensive taste landed him the nickname “Mad” King Ludwig. After sending the country into financial decline, a government commission declared Ludwig mentally unfit to serve as king of Bavaria in 1886.

The Hohenschwangau castle is slightly less known than Schloss Neuschwanstein, but is absolutely no less in terms of beauty and history. The castle was dated back to the 12th century, home to the knights of Schwangau. However, over the centuries, it was badly damaged.

From 1832 to 1836, the neo-Gothic castle was built by crown prince Maximillan of Bavaria from the ruins of the ruined castle Schwanstein. As noted above, King Ludwig II spent his childhood here and it served as the romantic summer and hunting residence for the Bavarian royal family.

After the demise of his father, King Ludwig II took over the castle and spent much of his time there.

The four striking corner towers and walls with battlements give the castle a medieval appearance. The design of the castle is in Biedermeier style and contains more than 90 murals by Moritz von Schwind and Ludwig Lindenschmit.

One of my favorite stories told by the Hohenschwangau castle tour guide was how the servants kept the stoves (there was one in just about every room – if not every room) lit. The royal family didn’t want the servants walking into the rooms, so the walls had secret (well, not so secret) passageways. The servants used these to feed wood (or whatever the source of fuel was) into the stoves without being seen. Our tour guide mentioned that the servants probably overheard a lot of good stories while doing so – and perhaps lingered inside the walls a bit longer than necessary to listen – which might have been the source of the phrase, “the walls have ears.” I don’t know if this is true, but I hope the servants enjoyed some juicy gossip now and again.

Here are our exterior shots, including the horse drawn carriage ride up to Neuschwanstein Castle (we walked down).

We stopped along the way between the castles to watch this gentleman make these yummy cheesy donut hole like things. They were good, but Michael proclaimed that he likes mini donuts better.

We walked to the lake – so pretty – then spent a bit more time in town (drinking hot wine and having a snack) before returning to the hotel. It was mostly a cloudy and chilly day (which didn’t make for excellent photos), but we truly enjoyed visiting and learning about the castles.

We took a day trip to Ulm the next day. I am including it in this post because Munich was still our home base.

We went to the Museum Brot and Kunst, a museum set over three floors exploring the art, history and craft of bread making, baking and milling. Then we walked around town a bit and ate a late lunch before taking the train back to Munich.

Here are a couple of pictures of bread. I know it is exciting. Try to remain calm. The plaque near the one on the left reads as follows: “The still life, very popular in Dutch 17th century painting, was imported into the German region by Georg Flegel. He established this art genre in Germany in the cities of Frankfurt and Hanau and paved the way for other artists such as Sebastian Stoskopff.”

Wheatfield – A Confrontation

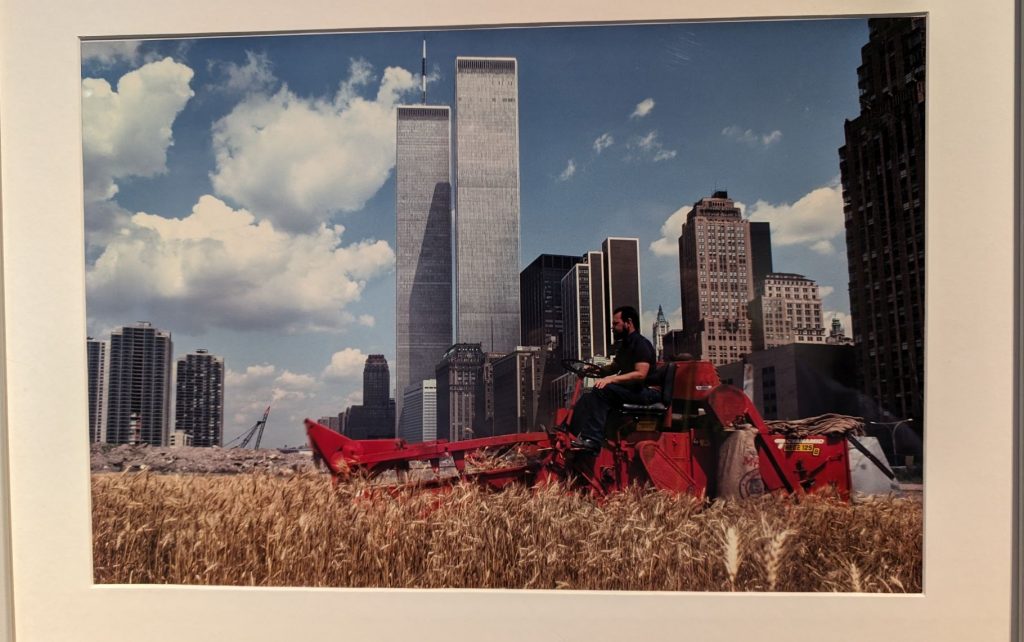

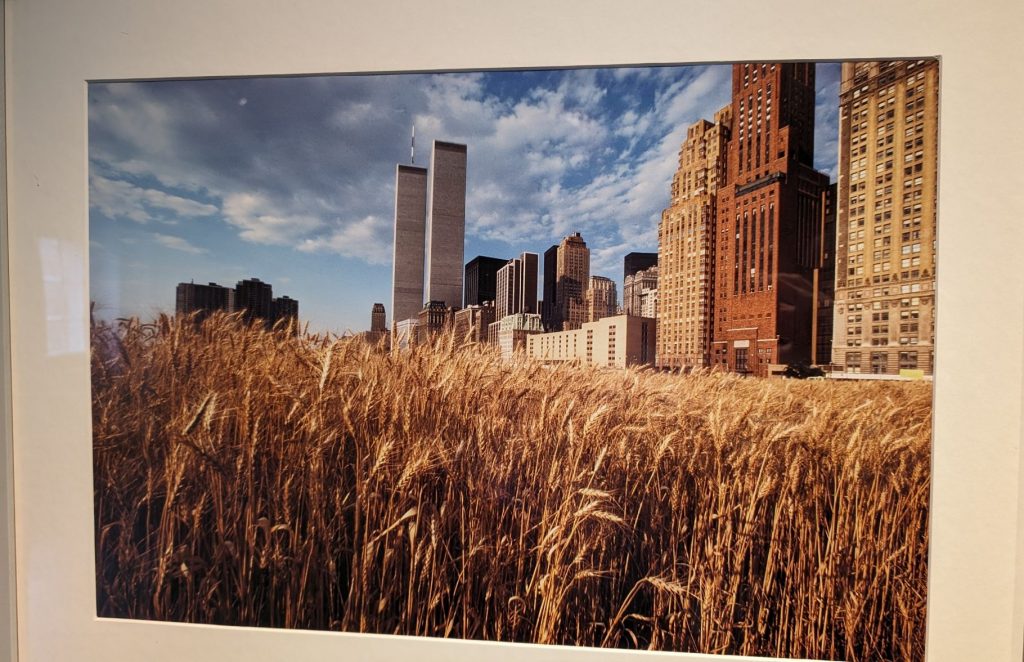

I am sharing this story and the accompanying two pictures because they are simply fantastic!

These photos document a spectacular Land Art Project. After months of preparation, in May 1982, Agnes Denes planted a two-acre wheat field on a landfill in lower Manhattan two blocks from Wall Street and the World Trade Center, facing the Statue of Liberty. Two hundred truckloads of dirt were brought in and 285 furrows were dug by hand and cleared of rocks and garbage. The seeds were sown by hand. The field was maintained for four months. The crop was harvested on August 16 and yielded over 1000 pounds of healthy, golden wheat.

Planting and harvesting a field of wheat on land worth $4.5 billion created a powerful paradox. Wheatfield was a symbol, a universal concept; it represented food, energy, commerce, world trade, and economics. It referred to mismanagement, waste, world hunger, and ecological concerns. It called attention to our misplaced priorities. The harvested grain traveled to 28 cities around the world in an exhibition called “The International Art Show for the End of World Hunger,” organized by the Minnesota Museum of Art (1987-90). The seeds were carried away by people who planted them in many parts of the globe.

There was a LOT more to the museum than this! So much history and chemistry and art. . . If you go to Ulm, you might want to visit it.

We also walked by Ulm’s Town Hall. The architecture is beautiful and it is covered by lovely paintings.

I should mention that we also saw Ulm Minster. The tower was closed and it was covered with a lot of scaffolding, so it wasn’t a pretty sight on our visit. I am sure it is lovely otherwise.

Here are a few pictures of the town. I thought it was the prettiest by the river.

One of my favorite things in Ulm, even though it was only a few-minute’s visit, was the Einstein Fountain.

Albert only lived in Ulm for 15 months of his 76-year life. He was born in Ulm on March 14, 1879, and his family moved to Munich on June 21, 1880. Einstein, a Jew, acted as a guarantor to help a number of persecuted people migrate to the USA during the Nazi era. Understandably, his relationship with Ulm remained tense after 1945. The city has long faced this uncomfortable part of its history.

We had a nice and reasonably priced meal at Extrablatt. The menu really is an entire newspaper’s worth of choices, as shown in this picture of Michael. We liked the decor as well, especially the signs posted on the pillars.

I just realized that this blog is already long enough. I am going to finish our report of Munich in the next blog!